I use empirical and theoretical approaches

to understand how species colonize new environments.

Biotic interactions and range limits

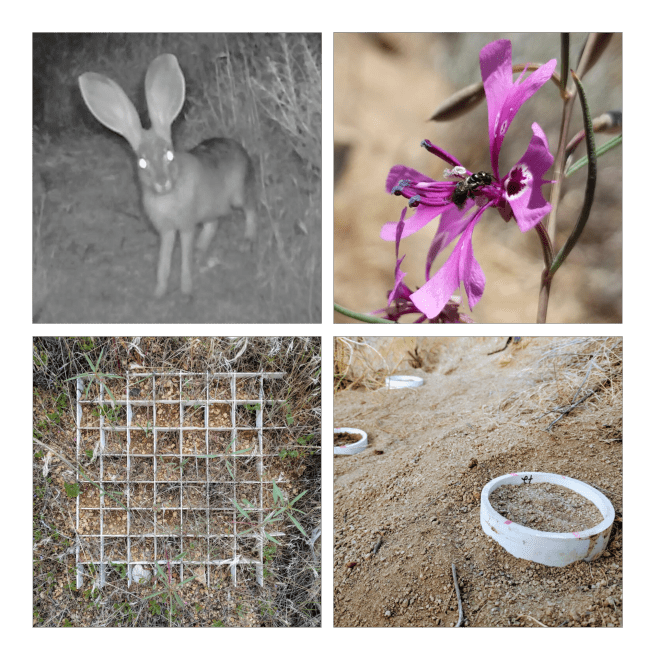

A species’ niche often manifests in space as the species’ geographic distribution. Thus species’ distributions are ecological patterns emerging largely from the evolutionary process of adaptation, with the limits of these distributions often reflecting the boundary between adaptation and maladaptation. But before we can assess why adaptation fails at a species’ range limit, we need to ask what environmental factors are actually constraining the species’ distribution — what is it about the environment beyond the range limit that prevents populations from establishing there? Surprisingly, it’s rare to have experimental tests of this question. Historically studies and models of species’ distributions have focused overwhelmingly on climatic variables, and species’ distribution models often assume purely climatic control on species’ ranges. However, most species are distributed over complex environmental gradients comprising changes in multiple biotic and abiotic variables. Transplant experiments, ideally combined with manipulations of putatively important environmental variables, are the most powerful method to test the relative influence of these variables on the location of the species’ range limit. In my dissertation, I used a variety of field and greenhouse experiments with the California native plant Clarkia xantiana ssp. xantiana (Onagraceae) to untangle complex environmental gradients and test key predictions from range limit theory, quantifying the relative influence of both biotic and abiotic factors on plant lifetime fitness inside and outside the subspecies’ geographic range limit.

Relevant papers:

- Benning, JW, Eckhart VM, Geber MA, and Moeller DA. 2019. Biotic interactions contribute to the geographic range of an annual plant: herbivory and phenology mediate fitness beyond a range margin. American Naturalist, 193:786-797. pdf

- Benning, JW and Moeller DA. 2019. Maladaptation beyond a geographic range limit driven by antagonistic and mutualistic biotic interactions across an abiotic gradient. Evolution, 73:2044-2059. pdf

- Benning, JW and Moeller DA. 2021. Microbes, mutualism, and range margins: testing the fitness consequences of soil microbial communities across and beyond a native plant’s range. New Phytologist, 229:2886-2900. pdf

- Benning, JW and Moeller DA. 2021. Plant-soil interactions limit lifetime fitness outside a native plant’s geographic range margin. Ecology, 102:e03254. pdf

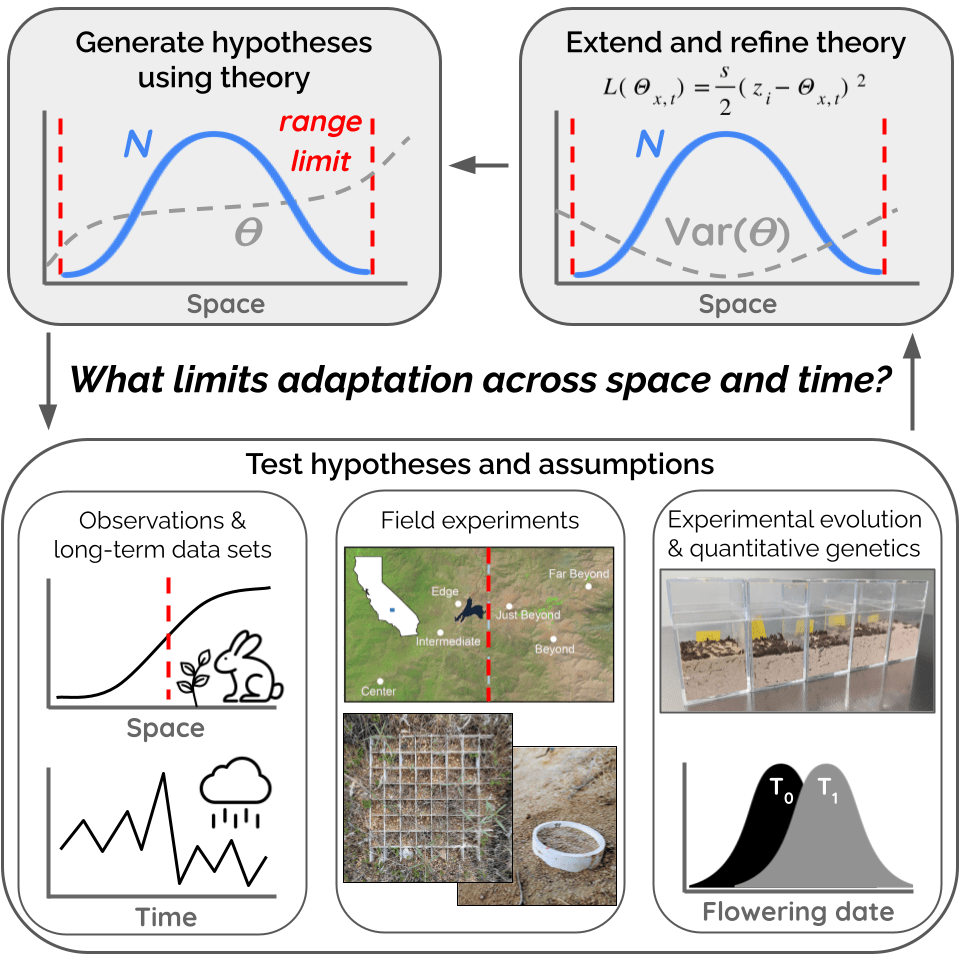

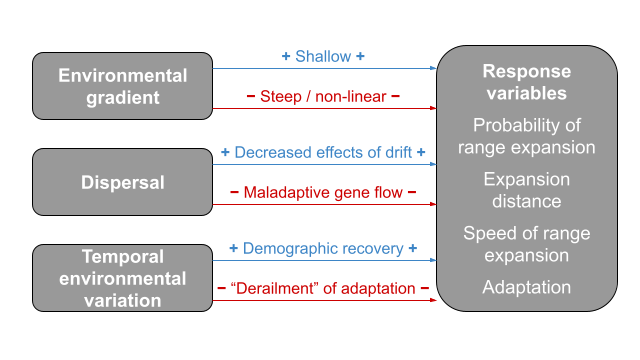

Testing and developing range limit theory

Theory has suggested that the shape of environmental gradients and the magnitude of dispersal play key roles in the probability of range expansion and the formation of stable range limits. However, we largely lack empirical tests of range limit theory. Furthermore, existing models do not account for many factors that we know to be common features of natural environments and systems, such as temporal environmental variation and heritable variation in dispersal. I use experimental evolution, genomic analyses, and novel models to

- test key predictions and assumptions of range limit theory

- further our understanding of how the interplay of environment, demography, and genetics determines ecological patterns through space and time

- work toward a spatio-temporal framework to help us understand species’ distributions in complex environments

Much of this work involves experimental evolution of flour beetles (Tribolium sp.) and microbes within simulated “landscapes” in the lab. This work has been supported by NSF PRFB and NSF DEB 2230806.

Relevant papers:

- Benning, JW, Hufbauer, RA, and Weiss-Lehman, C. 2021. Increasing temporal variance leads to stable species range limits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 289:20220202. pdf

- Benning JW, Clark EI, Hufbauer RA, and Weiss-Lehman C. 2024. Environmental gradients mediate dispersal evolution during biological invasions. Ecology Letters, 27:e14472. pdf

Tempo and mode of adaptation

What factors promote versus limit adaptation? General answers to this question are hard to come by — even for a well-studied process like gene flow, it is still difficult to predict when migration of alleles will encourage versus constrain adaptive evolution. Questions like this are not only of fundamental interest, but also have wide ranging implications for conservation and management of natural populations. I’m exploring themes related to the pace, pattern, and mechanisms of adaptation in several ongoing projects, including:

- Why do populations vary in their evolutionary responses to the same environmental perturbation? We used a resurrection approach, paired with quantitative genetic and long-term demographic data, to address this question in natural populations of Clarkia xantiana that recently experienced an extreme drought. Collab with Dave Moeller and stellar UMN undergrad Lex Faulkner.

- How does spatial and temporal environmental heterogeneity influence adaptation to novel environments? Along with modeling approaches, we’re using experiments to document adaptation in real time among flour beetle populations experiencing different patterns of spatio-temporal environmental variation. Collab with Topher Weiss-Lehman and awesome UW undergrads Alex Kissonergis and Annaliese Bronner.

Relevant papers:

- Benning JW, Faulkner A^, and Moeller DA. 2023. Rapid evolution during climate change: demographic and genetic constraints on adaptation to severe drought. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 290:20230336. pdf. ^ undergraduate mentee

- Gorton AJ*, Benning JW*, Tiffin PL, and Moeller DA. 2022. The spatial scale of adaptation in a native annual plant and its implications for responses to climate change. Evolution. 76:2916-2929. pdf. * equal contribution